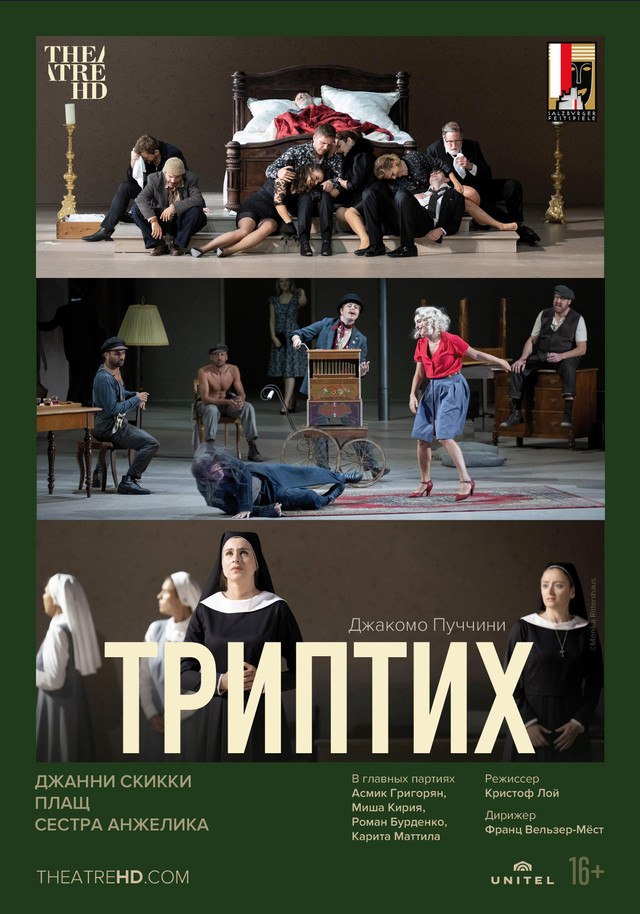

Written in the middle of the First World War, Il trittico was premiered in New York on 14 December 1918. In a time of crisis, in which all values are called into question, to a composer such as Giacomo Puccini, Dante’s Divina Commedia may have seemed a not-so-remote point of reference that could offer orientation.

Il trittico — ‘the Triptych’ — consists of three one-act operas which at first glance are unconnected with one another. However, a deeper exploration of the narrative structure reveals an overarching system of coordinates. Extending between heaven and hell, and a never-ending situation of waiting that perpetually promises a way out, i.e., purgatory, the three operas portray various facets of existence, individual fates from a world that seems to hold out little in the way of hope. The theme that links the works are systems — appearing each time in a different form and colour — in which individuals are trapped. What is being described here are the grinding mills of unfreedom.

In Gianni Schicchi, with its playful levity, peals of unbounded, strident laughter ring out — albeit of the kind that can only be heard in hell. We are in Florence, in the house of Buoso Donati, who has just died. Once the will has been found, his assembled kinsfolk — degenerate aristocrats — discover they have been deprived of their inheritance. After initial reluctance they bring themselves to seek assistance from an unpopular newcomer, the cunning Gianni Schicchi. He sets to work, ruthlessly turning the situation to his own advantage — not for nothing does he rage through Dante’s Inferno as a kind of sinister poltergeist. Gianni Schicchi destroys the system, breaking every taboo, paying no respect to life or death, and cheats the legacyhunters of their inheritance all over again — all in the spirit of black comedy. Schicchi’s daughter Lauretta is a young girl who is innocent of the felonious activity taking place around her. With her and her betrothed Rinuccio, a member of the Donati family, a new, perhaps better, time will dawn.

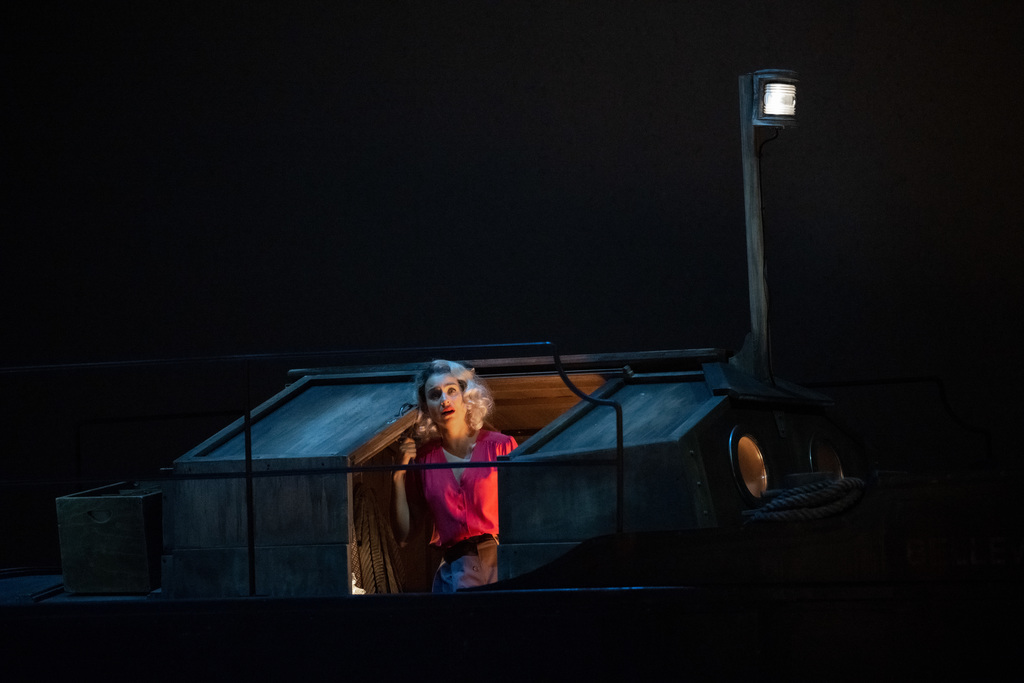

In Il tabarro (‘The Cloak’), surrounded by the decaying miasma of the Seine, we have arrived in purgatory on earth. Puccini sets the piece in the present day, in Paris, in a realistic, Simenon-like milieu of stevedores, drinkers and whores. In an oppressive atmosphere of hopelessness a love triangle arises between Giorgetta, her husband — the barge owner Michele — and his stevedore Luigi. Giorgetta is a woman with a history: she’s a mother who has lost a child and whose marriage is on the verge of breakdown. She starts an affair with Luigi, which gives her a momentary escape from the bleakness of her everyday life. But she is torn between the wish to rescue her marriage and her yearning to start a new life. Her jealous husband kills her lover, ending any dreams of happiness. Il tabarro fathoms the entire unremitting darkness of human existence.

In Suor Angelica the perspective has narrowed to the tragic fate of a single figure, the young nun Angelica. Banished to the convent for an indiscretion, she leads a joyless existence and waits for news of her son, whom she has been forbidden to see since his birth. When she learns that he has died, she resolves to put an end to her life. The climax of the opera is an extended monologue lasting 20 minutes in which Angelica works through her doubts as a devout Catholic and frees herself from her feelings of guilt and remorse. In a redemptive ending she finally transcends all her pain and escapes her agony. With a radiant finale Puccini opens up a path for her into the spheres of celestial paradise.